Journalists' rights to cover protests must be safeguarded

In late February, a protest erupted outside the Turkish Embassy in Finland, where a picture of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was set alight. Freelance photojournalist Miro Johansson, present to document the event, was detained by the police despite identifying himself as a journalist and offering to show his press card.

Initially, Johansson faced suspicion of defamation related to the burning of Erdoğan's picture, but the charges were promptly dismissed. However, his memory card was confiscated and only returned a week later upon request by the Union of Journalists in Finland's lawyer—by which time the story had lost its newsworthiness.

It is worth noting that merely capturing an image cannot be deemed defamation. Defamation would require, at the very least, using the photograph in some way. Consequently, it is clear that confiscating the memory card was an excessive and utterly disproportionate action by the police.

Protesters set fire to a picture of the Turkish President. Photo: Kurdistanin puolesta

This troubling incident reveals the potential threat that police actions pose to the freedom of photojournalists. The police's actions obstructed Johansson's capacity to report on a newsworthy event and earn a living, while also depriving the public of the opportunity to witness the protest through a professional photojournalist's perspective. With Johansson reportedly being the sole professional photographer at the scene, the incident was covered in the media using archive photos of the embassy and the president. This limited the public's ability to gauge, for instance, the proportionality of the police response.

In a parallel case at Aalistunturi, a documentary film crew led by Virpi Suutari was barred by the police from recording the dismantling of a tripod utilised by activists to block a road, citing “technical and tactical methods” as justification. Multiple law professors have stated that the police overstepped their authority.

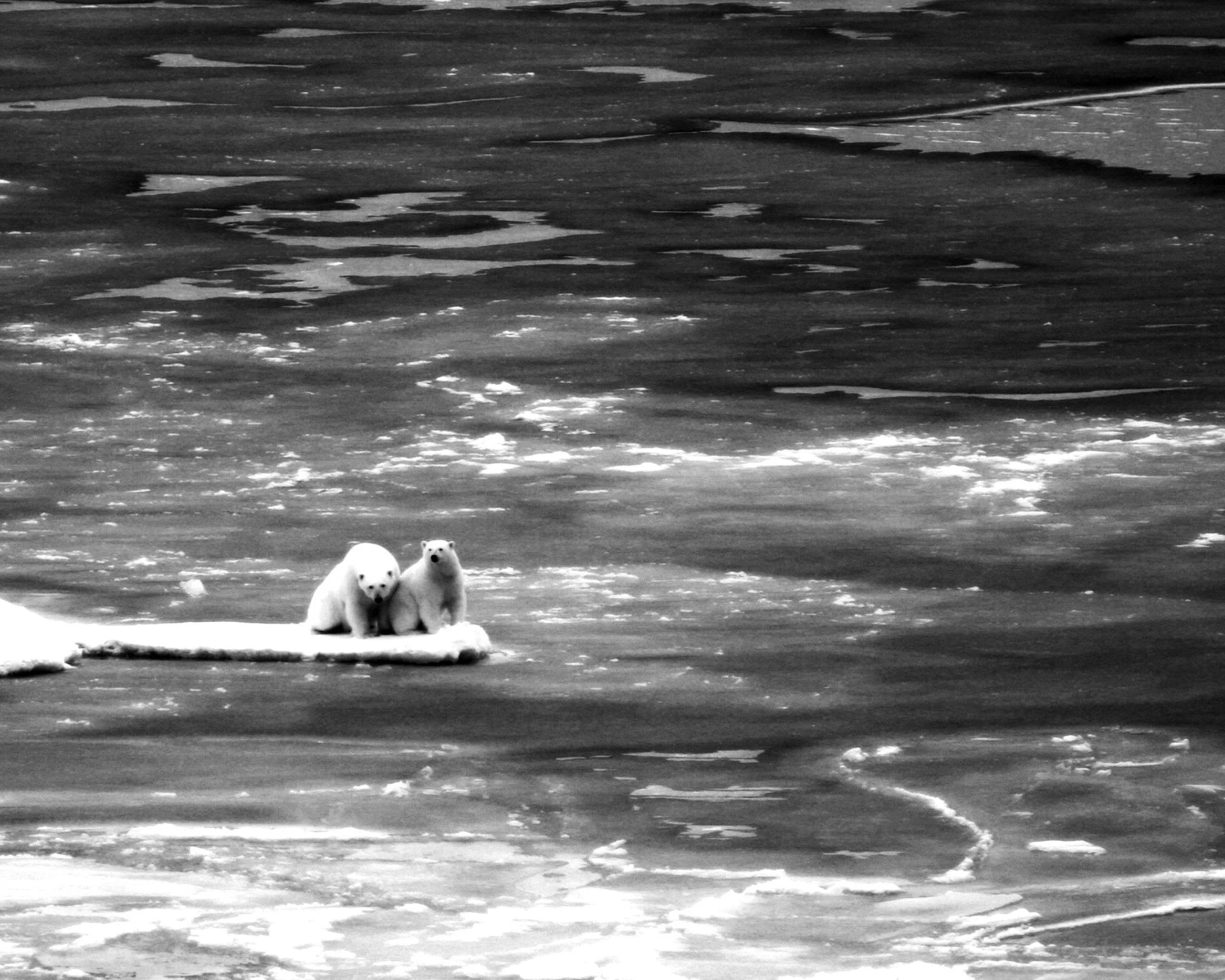

Protesters built tripods to block a road. Photo: Metäsliike

Restrictions on freedom of speech must always have a legal basis, and without a compelling reason, the police lack the right to interfere with recording. In exceptional cases, filming may be limited to ensure the safety of the arrestee, the police, or the public.

Public authorities bear the responsibility of ensuring the implementation of fundamental rights. Capturing photographs or recording protests falls under the exercise of freedom of speech protected by the Finnish Constitution. Moreover, freedom of expression and information is guaranteed by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union and the European Convention on Human Rights. The European Court of Human Rights has recognised that the gathering and dissemination of information, such as documenting protests, is an essential part of journalistic activity.

The incidents involving Miro Johansson and Virpi Suutari's film crew point to a troubling pattern of police interference in journalistic activities, which threatens the bedrock of democracy. Safeguarding journalists and preserving freedom of expression are vital to establishing an open and transparent society. When police actions disregard these core principles, they erode public trust and hinder the free flow of information. As such, it is crucial that authorities prioritise the protection of journalists' rights, ensuring that the public remains informed while consistently upholding the integrity of democratic values.