A family fleeing Kyiv is waiting to cross the border in Berehove, Ukraine on March 4. The estimated waiting time is ten hours.

When the terror began, they fled

In spring 2022, first thousands, then hundreds of thousands, and eventually millions of Ukrainians crossed the border to neighbouring countries in search of safety. Even more are living as internally displaced people.

HUNGARY, UKRAINE – On the 2nd of March 2022, in east Hungary, the main street of the small village of Barabás is calm, despite Europe going through its worst crisis since the Second World War. The border is just a few minutes’ drive away, and on the other side, in Ukraine, Russia’s brutal war of aggression is raging.

The local village house has been turned into a refugee shelter, where Ukrainians who have left their homes and crossed the border can find safety. From there, they continue towards the Hungarian capital Budapest.

Inside the village house, there are tired families, to whom volunteers are serving food and drinks. The journey has been long, but the children still have some energy left. They are colouring at the tables, and you can hear someone giggle.

Alina Zhuravlyova, 10, holds Emilia Skrypnychuk, 3, at an aid station in Barabás on March 2. Zhuravlyova came with her family from Zaporizhzhia near the Crimean Peninsula. She brought with her one toy and a colouring book which she gave to a girl without any toys.

Kristina Stoliarova is standing outside, and her eyes seem sore from crying. The young woman has fled Russian aggression twice already. In 2014, she left her home in Luhansk in east Ukraine. She thought she would be able to return home after three days.

The days turned into eight years, and Stoliarova settled in Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine. In February 2022, she had to flee again. Catching an evacuation train was not easy.

“People started to panic and run and push each other. There were men to whom we tried to tell that children must be protected first, then women and lastly men. Everyone was trying to save themselves,” Stoliarova says. She fled together with her mother and cat.

The northern reaches of the Carpathian Mountains stretch across western Ukraine.

At the Chop railway station on the Ukrainian side of the border, an elderly lady sat in a half-empty departure lounge introduces herself as Nadiya Petrovna Chiripovskaya. She says she had started her journey from the badly bombed Kharkiv.

Chiripovskaya describes the first strikes as loud and scary. The calendar says it is the 5th of March, but it is difficult for her to remember when the journey began: “My children just took me with them.”

Chiripovskaya left her home city of Kharkiv after the first attacks reached the city.

Many people leave the border crossing with a broken heart. Men are wiping their eyes and hugging low-spirited women and children, who are going to cross the border to Hungary and head to safety. Men of fighting age turn their cars around to cross the Carpathian Mountains, heading back to their homes and bases. No one knows when they can see their loved ones again – or whether this was a goodbye.

10-year-old Mariia Dushyna fleed with her family from Kharkiv the border town of Berehove.

Although millions of Ukrainians have left their home country, an even larger number of people are living as internally displaced people within the borders of Ukraine. In the border town of Berehove, a school hosts almost 80 internally displaced Ukrainians. There are five bunks beds placed in a small room, and a family of five sitting on them: father Kyryl Dushyn, mother Liubov, siblings Alisa and Mariia, and their cousin Daria Kalach.

The family used to work at a theatre in Kharkiv and fled west as soon as the bombings and shelling began. Many loved ones stayed behind.

“They are hiding in basements, staying at metro stations for various days and trying to find food in inconceivable ways,” says Kyryl Dushyn.

The family already misses having things to do. The following day, the father has a job interview, and the women are going to weave protective nets for the Ukrainian army.

Berehove normally has 24,000 inhabitants. Due to the war, many internally displaced persons have now arrived in the city.

The other family staying in the room has a small cat, and the animal is jumping from one bed to another. Larysa Tryamina, wearing a scarf around hear head, says that it took four days for the family to reach Berehove from Kharkiv.

“We’re happy to have a warm place to sleep, we get food three times a day, we can wash ourselves and do laundry.”

Tryamina has cancer. In Kharkiv, she was given treatment, but the hospital has been destroyed by bombs. Now she wonders if it would be possible to be admitted to a Hungarian hospital, but she is hesitant. The family members would end up apart because her partner must stay in Ukraine.

Before fleeing, Larysa Tryamina’s family spent four nights in the basement of their home during Russian bombing raid.

On the 11th of March, an air raid makes children and grownups jump out of their beds in Lviv, approximately 60 kilometres from the border with Poland. The time is 5:25, when the smartphone app starts to make a wailing sound. Quilted trousers on, coat on, two flights of stairs down, and to the basement door.

Two families with children come to the bomb shelter. One of the children is sneezing and coughing; another one finds a piece of chalk and draws a heart on the foundation of the shelter. Previously someone has played noughts and crosses on the staircase.

The girl continues her work tirelessly, and soon every stair in the bomb shelter is decorated with a lilac heart.

At 7:34, the app says that the danger is over.

A basement in Lviv, turned into a bomb shelter during air raids.

Later on the same day, in the buzz of the Lviv railway station, we meet Anna Shvidka, shivering in the station tunnel with her mother Natalia and cat Gorgik. The ginger animal leans firmly against Anna’s chest and trembles.

Anna Shvidka tells that they are going to cross the border, but they don’t know to which country. Maybe Slovakia, maybe Germany, depending on how full the trains are.

In the outskirts of Lviv, 6-year-old boy Kyryl Chernesky is leaning against a door frame with a grin on his face. He is full of energy, and he is jumping up and down in a room with mattresses on the floor. After fleeing Kyiv, the little rascal has spent four days in a refugee shelter at a church.

Next to him, his sister says that Kyryl probably does not understand they are escaping. Many parents tell a similar story: children see the situation as a peculiar holiday, and they continue playing whenever an opportunity arises.

Kyryl Chernesky, 6, is happy to find a place to play after leaving his home in Kiev.

Natalia Karpienko and her 9-year-old son Igor are staying in the room next door. On the bed lies the youngest guest of the shelter, Nastia. The two-month-old smells of sweet breastmilk, and she is making happy sounds. Her small feet are kicking inside the playsuit, and there is a white beanie on her head.

Karpienko says they have come from the Kyiv region, near Boryspil. “When the bombings started at night, I didn’t know where to go. I was scared that our house would be destroyed. In this shelter I feel safe.”

Angel-shaped Christmas lights watch over the streets of Lviv in Western Ukraine.

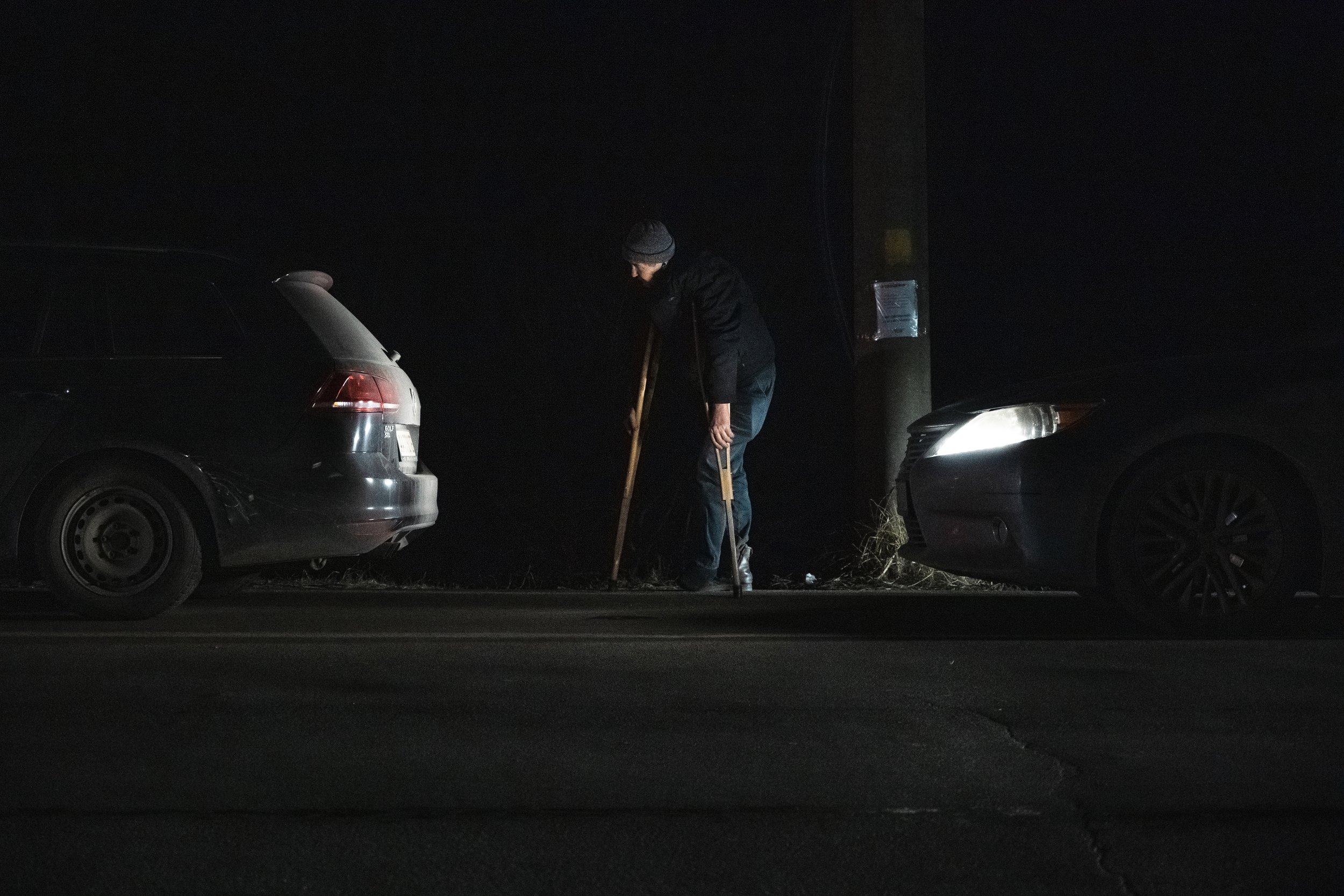

After mid-March, people have been fleeing the war for the fourth consecutive week. The border crossing between Hungary and Ukraine is now controlled by women in military outfits.

The border town of Berehove is full of internally displaced Ukrainians. Aid organizations are supporting refugees with food and material deliveries. The hardest work is done by local volunteers, who have been working around the clock for weeks to help refugees.

A school kitchen in Berehove feeds 400 refugees a day.

The kitchen at a refugee shelter set up in a school is managed by Ivanna Kobylyanska. She has worked in the same kitchen for 27 years already, but now she is feeding refugees instead of school children. Kobylyanska’s son went to fight in Kyiv, so she wanted to do something useful; hence, she continued to work in the kitchen without pay.

Now Kobylyanska and her team prepare 400 meals a day to fill the stomachs of refugees. Just a month ago, she was feeding 40 school kids. She starts her days in the kitchen at 6 in the morning and goes home at 11 in the evening.

“But it’s not a big deal,” Kobylyanska notes and smiles, “it’s just routine.”

The war in Ukraine began on February 24th. Over 10 million people have fleed both inside and across the borders of Ukraine.

On the top floor of the school, there is still the theatre family from Kharkiv we met weeks ago. Mother Liubov Dushyna is worried, because for a few days the family has not been able to contact friends in Mariupol.

Larysa Tryamina, the cancer patient staying in the same room, has been admitted to a hospital in a nearby town. Her husband and daughter have stayed at the shelter, as has their cat Bella. Bella is walking on the bed frame and playfully pokes her paws towards the guests.

Mariia Dushyna and her older sister had 20 minutes to pack their bags. Mariia brought a phone and a few soft toys.

Liubov Dushyna says that her husband has not managed to find work yet. The future seems hazy, but three weeks at the shelter has made the family consider what to do next. She has been toying with ideas: maybe Poland, if she can find a suitable art project.

In mid-April, a message arrives. Daria Kalach from the theatre family has gone to Italy to try her wings. The father has stayed in Berehove and the others are in Georgia.

text: Ulriikka Myöhänen

photos: Antti Yrjönen