Dreams at stake

The covid-19 pandemic has derailed the lives of young people in South Sudan, a country recovering from a civil war.

Rose Night started school at the age of nine. Her dream is to become a lawyer.

YEI, South Sudan – Wild vegetation surrounds crumbled, abandoned mud huts. Scattered around, there are the remains of cars, stripped of wheels and other removable parts. Empty houses are missing their most valuable parts: tin roofs and windows.

The surge in returnees that accelerated prior to the Covid-19 pandemic has not repaired the damage caused by the 2016 civil war around the city of Yei. “The sight is still stomach-churning for those returning to the region,” says 29-year-old Viola Jabu. “When we decided to return, I was afraid there’d be no one in Yei.”

She began the journey home from a Ugandan refugee settlement with nine children and adolescents in February 2020, right before the pandemic hit. “I was relieved to see plenty of life on the streets. However, our home had been destroyed.”

In Yei every plot that can be used for growing is utilised.

Viola Jabu and her family have settled behind an abandoned petrol station on a busy street. The suitcases and bags, in which the family has packed their entire life, are neatly piled in the children’s bedroom. The parents sleep in a storage room, lit by the light coming in through a tiny window.

“We returned from Uganda because life as a refugee was tough. It was difficult to find food and work and the children were often ill. My husband lived here already and told us that it’s safe now,” Jabu tells.

“We couldn’t have imagined that we’d have to face a pandemic, too.”

The schools in South Sudan were opened in May 2021.

Across the street is St. Joseph’s s school where 21-year-old Rose Night began her sophomore year as a secondary school student. Rose lives with her uncle, Viola Jabu’s partner Woi Wilson. Rose’s parents abandoned her when she was a child; her father disappeared, and her mother moved to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Wearing her school uniform, Rose has patiently listened to our conversation for over an hour. Then she can no longer wait. “When are you going to ask me something?” she asks. It is uncommon for students to volunteer for interviews unprompted.

“School has taught me that one must be courageous and study a lot, so that it’s possible to make one’s own decisions in life. With the help of education, you can find work and look after yourself,” she quotes her teachers.

Rose started school at the age of nine with support from her uncle, and her dream is to become a lawyer. Her uncle hopes Rose will one day study at a university.

Rose’s schooling already came to a halt when the family fled to Uganda. After returning to South Sudan, she was in school for just two weeks before the schools were closed.

“We were told to stay at home and be patient, but there was nothing to do. I was sad.”

Rose Night prepares for the first exam week in 18 months.

In South Sudan, the opportunities to switch to remote learning were non-existent, which is why many children and adolescents had their education intrerrupted for over a year. In a country that has already suffered from a civil war, it is estimated that 2.2 million children did not go to school before the pandemic, and according to an estimate by UNICEF, the pandemic doubled the number to 4.3 million.

Viola Jabu and Woi Wilson organised home schooling for the children, so that they would not forget the importance of education in pursuing their dreams. Everywhere in the world, the lives of the young are full of temptations.

“Young people started to act up, run off from home at night, party and drink and consume other drugs. I didn’t do like the others and that’s why some distanced themselves from me,” Night says.

“Young people no longer knew where their lives were headed.”

Yei is the third largest city in South Sudan.

Yei is the third largest city in South Sudan and strategically important for commerce due to its location near the borders to both the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda.

The countyside surrounding the city is known as the granary of South Sudan, and in peacetime Yei can ensure the availability of food in the entire country.

The current peace agreement has been in force for over three years, yet outside the city there are still armed groups that have not signed it. The residents cannot go to the vast fields in the villages, so it is common to see corn planted on roadsides all over the city.

A bullet-hole scars the blackboard.

For years the residents of Yei have persisted in the face of various threats. On top of war, there is disease. A poster on the wall of a centre that registers returning migrants encourages getting vaccinated against polio. South Sudan is one of the few countries in the world in which the disease has been resurgent in recent years.

Another poster explains the symptoms of Ebola and emphasises the importance of hand hygiene in stopping its spread. It resembles a newer poster next to it, which explains how to avoid catching Covid-19.

The most significant consequences of the current pandemic are linked to livelihood and education. Globally, the UN estimates that the pandemic has pushed tens of millions of families to the brink of extreme poverty.

After the schools were closed, teachers had to find other jobs and many students have had to support their families by working.

“Samuel buys food for his siblings with the money he’s saved for school. I feel sad seeing him go job hunting instead of school,” says Samuel Ayki’s mother Mary Aziyo.

18-year-old Samuel Ayki toils away at a vegetable plot with his two brothers. It has only been two weeks since the beanie-wearing young man returned to Yei. Ayki spent the early stages of the pandemic as a refugee in Uganda, where school closures lasted for 80 weeks, longer than anywhere else in the world.

His mother Mary Aziyo lost her income when the local market at the refugee settlement was closed because of the restrictions on movement.

Ayki was due to finish comprehensive school in spring 2020. “Covid ruined my schooling. It feels like my brain became blunt because I wasn’t able to learn anything new.”

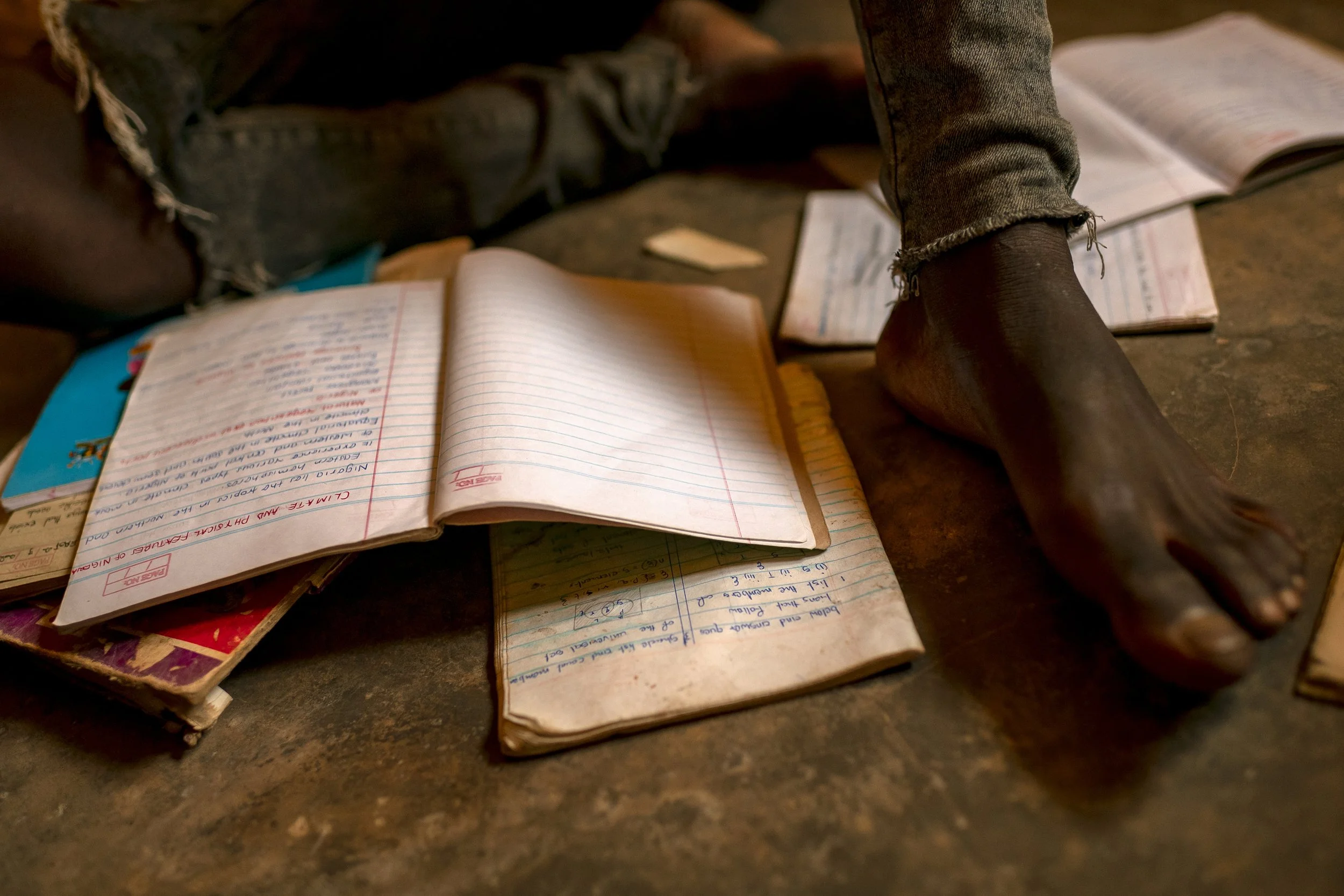

“Sometimes I try to study on my own using the notebooks I brought back with me from Uganda,” Samuel Ayki tells.

Samuel Ayki plans to save money to return to school.

In South Sudan, schools reopened in May 2021 and Ayki’s friend who had gone back to school in Yei encouraged him to return home.

However, all related costs – such as learning materials and school uniforms – were such a huge expense for a poor family that they could not afford them. The family needed the money Ayki was able to make doing odd jobs here and there.

Ayki plans to save money to return to school. Work is difficult to find, as he has been away from the city for a long time and the pandemic has impoverished businesses. “I’m sad seeing my friends and neighbours go to school, when I’m just looking for work or sitting at home. Sometimes I try to study on my own using the notebooks I brought back with me from Uganda.”

Samuel Ayki’s friend Peter Alison goes to school. In Yei, students stand out because of their uniforms.

Having fewer and fewer opportunities for making a living has driven families to desperate decisions. Many girls have had to get married because marriages benefit families financially.

Child marriages were a severe problem in South Sudan already prior to the pandemic; almost every other girl married underage, and now the number of child brides and teenage pregnancies has only gone up.

Getting pregnant almost always means that the girl drops out of school, and the consequences are drastic when it comes to continuing education. Rose Night’s best friend did not return to the classroom when the schools reopened their doors.

“She decided to get married. Now she has a baby and can’t return to school. I don’t know what that means to her future, but I miss her.”

Rose Night and other students have their temperature taken. Everyone must wear a mask.

Working as a grocer, uncle Woi Wilson’s livelihood has been dependent on the road running to the capital Juba and the neighbouring Uganda. Due to the pandemic, the traffic of goods slowed down, resulting in less income for sellers and higher prices for food. After a long struggle, Night is preparing for her first exam week in 18 months.

Students are waiting by the gates of St. Joseph’s school, where a guard takes their temperature and checks everyone is wearing a face mask. Fortunately, there is one to spare for a girl who has left hers at home.

“At school I feel safe. Learning brightens my mind and gives meaning to my days.”

School-related costs, such as learning materials and school uniforms, can be too expensive for a poor family.

text: Erik Nyström

photos: Antti Yrjönen